Page 22 - Breath of the Bear

P. 22

photos and story by Deby Dixon

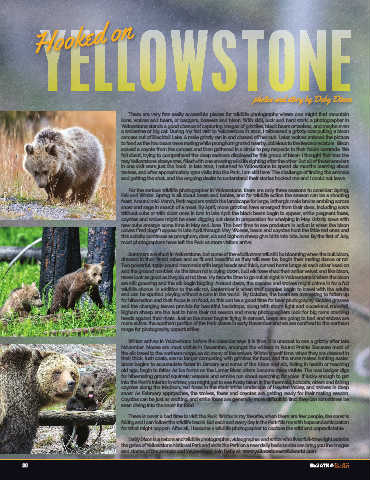

There are very few easily accessible places for wildlife photography where one might find mountain

lions, wolves and bears, or badgers, beavers and bison. With skill, luck and hard work, a photographer in

Yellowstone stands a good chance of capturing images of grizzlies, black bears or wolves, and maybe even

a wolverine or big cat. During my first visit to Yellowstone in 2010, I witnessed a grizzly sow pulling a bison

carcass out of Blacktail Lake. A male grizzly ran in and chased off her cub. Later, wolves entered the picture

to feed as the two bears were mating while pronghorn grazed nearby, oblivious to the fierce predators. Bison

scared a coyote from the carcass and then gathered in a circle to pay respects to their fallen comrade. We

fell silent, trying to comprehend the deep sadness displayed by this group of bison. I thought that was the

way Yellowstone always was, filled with one amazing wildlife sighting after the other. But all of those wonders

in one visit were just the hook. In late 2012, I returned to Yellowstone to spend six months learning about

wolves, and after approximately 1500 visits into the Park, I am still here. The challenge of finding the animals

and getting the shot, and the ongoing desire to understand their stories hooked me and I could not leave.

For the serious wildlife photographer in Yellowstone, there are only three seasons to consider: Spring,

Fall and Winter. Spring is all about bears and babies, and for wildlife action the season can be a shooting

feast. Around mid-March, Park regulars watch the landscape for large, lethargic male bruins ambling across

snow and sage in search of a meal. By April, more grizzlies have emerged from their dens, including sows

without cubs or with older ones in tow. In late April the black bears begin to appear, while pregnant foxes,

coyotes and wolves might be seen digging out dens in preparation for whelping in May. Grizzly sows with

new cubs emerge some time in May and June. The best time to see predators in action is when the bison

calves (“red dogs”) appear in late April through May. Wolves, bears and coyotes hunt the little red ones and

this activity continues as pronghorn, deer, elk and bighorn sheep give birth into late June. By the first of July,

most photographers have left the Park as more visitors arrive.

Summers are short in Yellowstone, but some of the wildflowers will still be blooming when the bull bison,

TM

dressed in their finest robes and as fit and beautiful as they will ever be, begin their mating dance or rut.

Two powerful, 1500-pound mammals with large heads and thick, curved horns lunge at each other head on

and the ground rumbles. As the bison rut is dying down, bull elk have shed their antler velvet and like bison,

never look as good as they do at rut time. My favorite time to go out at night in Yellowstone is when the bison

are still groaning and the elk begin bugling. Around dawn, the coyotes and wolves might chime in for a full

wildlife chorus. In addition to the elk rut, September is when wolf puppies begin to travel with the adults

and can be spotted playing without a care in the world. By October, the bears are overeating to fatten up

for hibernation and their focus is on food, so this can be a good time for bear photography. Golden grasses

and the changing leaves provide for beautiful backdrops, along with storm light and occasional snowfall.

Bighorn sheep are the last to have their rut season and many photographers look for big rams crashing

heads against their rivals. Just as the snow begins flying in earnest, bears are going to bed and wolves are

more active, the southern portion of the Park closes in early November and we are confined to the northern

range for photography opportunities.

Winter arrives in Yellowstone before the calendar says it is time. It is unusual to see a grizzly after late

November. Moose are most visible in December, amongst the willows in Round Prairie. Because most of

the elk travel to the northern range, so do many of the wolves. Winter is wolf time, when they are dressed in

their thick, lush coats, are no longer competing with grizzlies for food, and the snow makes hunting easier.

Snow begins to accumulate faster in January and some of the bison and elk, failing in health or reaching

old age, begin to falter. As ice forms on the Lamar River, otters become more visible. The rare badger digs

for hibernating ground squirrels; weasels and ermine run about searching for voles. If lucky enough to get

into the Park’s interior in winter, you might get to see frosty bison in the thermals, bobcats, otters and fishing

coyotes along the Madison, red foxes in the stark white landscape of Hayden Valley, and wolves in deep

snow. As February approaches, the wolves, foxes and coyotes are getting ready for their mating season.

Coyotes can be just as exciting, and while foxes are generally more difficult to find, they can sometimes be

seen diving into the snow for food.

There is never a bad time to visit the Park. Winter is my favorite, when there are few people, the snow is

falling and I can follow the wildlife tracks. But each and every day in the Park fills me with hope and anticipation

for what might happen. After all, I became a wildlife photographer to capture the wild and unpredictable.

Deby Dixon is a nature and wildlife photographer, videographer and writer who lives full-time right outside

the gates of Yellowstone National Park and visits the Park on a near daily basis so she can bring you the images

and stories of the animals and Yellowstone. Join Deby at: www.yellowstoneswildworld.com.

20